Have we already hit the peer review breaking point?

What does scientific publishing look like if every paper is AI-generated or at least AI co-authored?

Last week I attended the Future of scientific publishing conference organized by the Royal Society. I went to something similar a decade ago, which made me ponder what we were suggesting would be the future versus what has actually come to reality. I think that can be summed up as ‘the establishment of preprints and open data’. We still dream of real-time release of information from labs around the world, with post-publication peer review, and we may get there.

However, there were two comments at the conference that really played on my mind. First was the sentiment that came up in a few panel discussions that we may be overestimating the effects of AI on scientific publishing. I feel quite the opposite. I think we are underestimating the effect of AI on scientific publishing. If we look 10 years into the future, what will AI change? For those thinking it is as monumental a shift as the web, that didn't change too much about the way academics disseminate their research. We now just publish PDFs on the web instead of printing them out and sending them around the world. What makes AI different is that it's already affecting content creation. What does the web look like if all content is bot-produced? What does scientific publishing look like if every paper is AI-generated or at least AI co-authored? This brings me to the other comment that weighed heavy on my mind.

"Elsevier fielded 3.5M submissions, published 700K and saw +600K increase in submissions year on year"

This is a 17% increase in submissions at the biggest academic publisher by volume in the world. Because Elsevier is indeed the largest publisher, with many journals from varying fields with varying rejection rates, I decided to assume it offers a good average for academic publishing writ large, and my mind began to extrapolate.

The 600K increase in submissions year-over-year is staggering. That's roughly a 17% growth rate, which is double the historical academic publication growth rate of 8-9%.

Based on the current model, the peer review system becomes mathematically impossible remarkably quickly. If we assume each paper needs 2-3 reviews and there are roughly 20 million active researchers globally who could potentially serve as reviewers, we hit a crisis point for submissions quite quickly. And this is assuming a steady, not exponential, growth curve for the number of papers submitted each year. Of course, if you had said to publishers in the year 2000 that the number of articles published each year would quadruple by 2025, they may have suggested that peer reviewing that volume would be untenable - but that was before papers could be written in a minute.

If publications grow 10x within 5 years of AI adoption, we'd need 200-300 million peer reviews annually. Even if every PhD-level researcher worldwide dedicated their entire career to reviewing, we couldn't keep up. As acceptance rates plummet (potentially from 20% to 5-10%), authors may submit each paper to more journals. This means the same research generates multiple submissions, artificially inflating the crisis.

This brings us to a fascinating question about value creation. In our current system, we reward the person who writes the paper. They get citations, tenure, grants. But in an AI-dominated world, who deserves credit? Will we have academic prompt engineers? Will we have raw data creators?

So assuming peer review is at breaking point or not far off, perhaps the most obvious near-future change to scientific publishing is the widespread adoption of the "publish then curate" model. We have the tech stack to publish preprints, we have overlay journals, and we have eLife's innovative new model. What will it take for other publishers to realise the writing is on the wall?

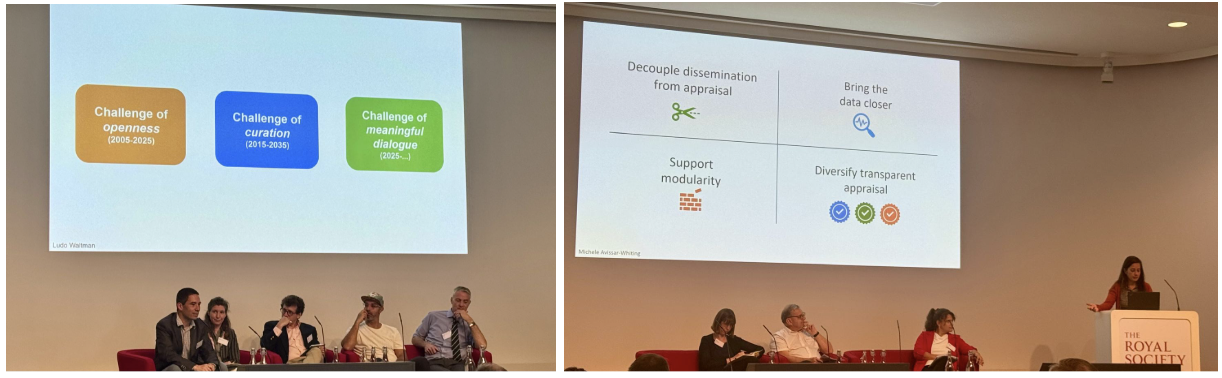

Two of the panels at the conference spoke about what comes next in a similar vein, with Professor Ludo Waltman of Leiden University highlighting that we now have the challenge of curation. Dr. Michele Avissar-Whiting of Howard Hughes Medical Institute spoke of decoupling dissemination from approval.

I often feel disheartened at events like this, thinking there isn't enough innovation, but perhaps the wave of innovation that the web indirectly caused in scholarly publishing (see preprints and open data) is about to be repeated with AI. And this is enough to help make a more equitable academic publishing future whilst accelerating the pace of research for the good of humanity. And that is good enough for me.

Ps. Depending on how bullish you are on AI - you can predict when we hit breaking point in the model below: